- Home

- Yvonne Howell

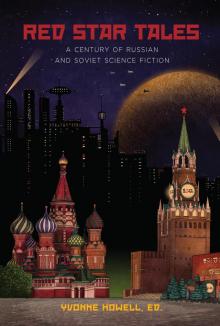

Red Star Tales Page 7

Red Star Tales Read online

Page 7

Taking the essential things from the cellar, so as not to die of hunger and thirst, we set off on an extended trip towards the Moon’s pole and into the other hemisphere, which had not yet been seen by any human being.

“Shouldn’t we follow the Sun westward?” suggested the physicist, “altering our course a bit towards one of the poles? Then we can kill two birds with one stone: the first bird is to reach the pole and the dark side; the second bird is to escape the excessive cold, since if we don’t lag behind the Sun we can run through places the Sun has warmed for a certain time – therefore, through places with an unchanging temperature. We can even change temperature on demand, to the extent we need to – if we catch up to the Sun, we can increase it; if we hang back, we can decrease it. This is especially good if you keep in mind that we’ll be approaching the pole, whose average temperature is low.”

“Oh come on, is that possible?” I remarked, in reaction to the physicist’s strange theories.

“Entirely possible,” he answered. “Just take into account the ease of running on the Moon and the apparently slow movement of the Sun. In actual fact, the greatest lunar circle is about ten thousand versts in length. This length has to be covered, if we don’t want to fall behind the Sun, in thirty days, or seven hundred hours, to express myself in earthly language. That means, in an hour we have to cover fourteen and a half versts.”

“Fourteen and a half versts per hour on the Moon!” I exclaimed. “I regard that figure with nothing but disdain.”

“Well, there you go.”

“We’ll run twice as far without even trying!” I continued, remembering our mutual gymnastic exercises. “And then every twelve hours we can sleep for just as long…”

“Different latitudes,” the physicist explained. “The closer we get to the pole, the less distance, and since we’ll head precisely in that direction, then we can run more and more slowly without falling behind the Sun. However, the cold of the polar countries won’t allow us to do that: as we approach the pole, in order not to freeze, we’ll have to move closer to the Sun, that is, run through places that have been exposed to extended illumination by the Sun, even though they’re polar. The polar Sun hangs low over the horizon, and therefore the ground is heated incomparably less, so even at sunset the ground is merely warm.”

The closer we get to the pole, the nearer we must be to the sunset, to keep a constant temperature.

“Westward, westward!”

We glided like shadows, like phantoms, silently touching the pleasantly warming ground with our feet. The moon was almost full and therefore shone exceedingly brightly, presenting an enchanting picture, veiled by blue glass that seemed grow thicker towards the edges, since it gets darker the closer it is to the edge. On the edges themselves you couldn’t make out either dry land, or water, or cloud formations.

Now we were seeing the hemisphere that’s rich in dry land; in twelve hours it would be the opposite, the half rich in water – almost nothing but the Pacific Ocean. It reflects the sun’s rays poorly, and therefore if it weren’t for the ice and clouds, which gleamed brightly, the moon wouldn’t have been as bright as it was now.

We easily ran up onto an elevation and even more easily down from it. From time to time we were bathed in shadow, from which more stars were visible. For now we encountered only low hills. But even the highest mountains would present no obstacles, since here the temperature of a place didn’t depend on its elevation: the mountaintops were just as warm and free of snow as the low valleys… Uneven places, protuberances, abysses on the Moon were not frightening. We leapt across uneven places and abysses as wide as ten or fifteen sazhens; if they were very wide and inaccessible, then we tried to run around on one side or we stuck to the slopes and protuberances with the help of thin cords, sharp hooked sticks and shoes with cleats.

Remember our low weight, which didn’t require cables for support – and it will all make sense to you.

“Why aren’t we heading for the equator? After all, we haven’t been there,” I remarked.

“Nothing is stopping us from going there,” the physicist agreed.

And we immediately changed our course.

We ran exceedingly fast, and therefore the ground got warmer and warmer; finally it became impossible to run because of the heat, for we had come to the parts that were more heated by the Sun.

“What would happen,” I asked, “if we ran, regardless of the heat, at this speed and in this direction – towards the west?”

“After about seven earth days we would see first the sunlit mountaintops and then the Sun itself, rising in the west.”

“But surely the Sun wouldn’t rise where it usually sets!” I was dubious.

“It’s true, and if we were folkloric salamanders, protected against fire, we could let our own eyes persuade us of this phenomenon.”

“What happens then? The Sun just appears and then disappears, or does it rise in the usual way?”

“As long as we run along the equator, let’s say, faster than fourteen and a half versts, the Sun will keep moving from west to east, where it will set. But we just have to stop, and it will immediately start moving in the usual way and, after we forced it to rise in the west, it will once again disappear behind that horizon.”

“But what if we ran neither faster, nor slower than fourteen and a half versts per hour, what would happen then?” I went on asking.

“Then, as in the time of Joshua, the Sun would stop in the sky and day or night would never end.”

“Can you play this sort of trick on Earth too?” I persisted to my physicist.

“Yes, but only if you’re in shape to run, ride or fly over the Earth at a minimum speed of one thousand five hundred and forty versts per hour.”

“What? Fifteen times faster than a blizzard or a hurricane? No, I won’t try that… that is, I forgot – I wouldn’t try it!”

“That’s right! What’s possible here, and even easy, is entirely unthinkable over there on that Earth,” and the physicist pointed at the moon in the sky.

So we reasoned, sitting down on the stones, for we couldn’t run any more due to the heat, which I already mentioned.

Worn out, we soon fell asleep.

We were awakened by a significant chill. Leaping up cheerfully and jumping up five arshins or so, we once again ran off towards the west, tending towards the equator.

You’ll remember that we had determined the latitude of our cabin as forty degrees, and therefore there was a fair distance left to the equator. But don’t think that a degree of latitude is the same on the Moon as on Earth. Don’t forget that the Moon’s size is proportionally smaller than the Earth, as a cherry is to an apple. Therefore, a degree of Moon latitude is no more than thirty versts, while on Earth it is a hundred and forty.

We became convinced, however, that we were approaching the equator by the fact that the temperature of the deep crevasses, which represented the average temperature, gradually increased and, after reaching fifty degrees Réaumur, stayed at that level. Then it even began to decrease, indicating that we had passed into the other hemisphere.

We determined our location more exactly by astronomical means.

But before we crossed the equator, we encountered many mountains and dry “seas.”

The form of lunar mountains is perfectly familiar to inhabitants of the Earth. For the most part they are round mountains with craters in the center.

The crater was not always empty, and did not always turn out to be a recent crater: sometimes a whole other mountain rose in the center with its own indentation, which turned out to be a newer crater, but very rarely an active one – with lava inside, glowing dull red on the very bottom.

Was it not these volcanoes that in the past had tossed up most of the rocks we often found? I can’t imagine they came from anywhere else.

Out of curiosity, we intentionally ran past the volcanoes, right along their very edges, and twice as we glanced into their craters we saw waves of

gleaming lava.

Once we even noticed an enormous, high sheaf of light above the summit of one mountain, most likely formed of stones heated until they glowed: the tremor from their fall reached our feet, which were so light here.

Whether in consequence of the lack of oxygen on the Moon, or for other reasons, we only came across unoxidized minerals, most often aluminum.

The low, even spaces, the dry “seas” in some places, despite the physicist’s assurances, were covered with clear, though small signs of neptunic activity. We liked that kind of depression, slightly dusty to the touch of our feet; but we ran so fast that the dust remained behind and dissipated at once, since it was not raised by the wind and didn’t blow into our eyes and noses. We liked the “seas” because we had pounded our heels on the rocky places, and for us they stood in place of soft carpets or grass. This sedimentary layer could not hamper our pace because of its thinness, which did not exceed a few inches.

The physicist pointed something out to me in the distance, and I saw to our right something like a bonfire that sent red sparks flying in all directions. The sparks traced out red arcs.

We tacitly agreed to make a hook in our path, so we could find an explanation for this phenomenon.

When we ran up to the place we saw scattered pieces of more or less molten iron. The small pieces had already managed to cool, the large ones were still red.

“This is meteoric iron,” said the physicist, picking up one of the cooled fragments of the aerolite. “The very same kind of pieces fall on the Earth,” he continued. “I’ve seen them more than once in museums. Only the name of these heavenly stones, or rather bodies, is incorrect. The name meteorite is especially inappropriate here on the Moon, where there’s no atmosphere. They aren’t even visible here until they hit the granite ground and get hot as the energy of their motion is converted into heat. On Earth they’re visible almost the moment they enter the atmosphere, since they’re heated by the friction of the air.”

After running across the equator, we decided to turn back towards the north pole.

The cliffs and mounds of stones were amazing.

Their forms and positions were quite bold. We had never seen anything like them on Earth.

If we imagined them there, I mean on your planet, they would inevitably collapse with a terrible crash. Here the capricious forms could be explained by the low gravity, which couldn’t pull them down.

We ran and ran, moving closer and closer to the pole. The temperature in the crevices grew lower and lower. On the surface we didn’t sense that, because we were gradually catching up to the Sun. Soon we were due to see its miraculous rise in the west.

We didn’t run fast; there was no need.

We had stopped going down into the crevices to sleep, because we didn’t want cold; instead we rested and ate where we stopped.

We also dozed off as we were walking, giving ourselves over to disconnected daydreams; there’s no reason to be surprised at that, knowing that similar phenomena have been observed on Earth. They’re all the more possible here, where standing takes little more energy than it takes to lie there (speaking in terms of weight).

VI

The moon sank lower and lower, illuminating us and the lunar landscape more weakly and then more strongly, depending on which side was turned towards us – the watery one or the land one, or on how much of its atmosphere was full of clouds.

There came a time when it touched the horizon and began to sink behind it – that meant we had reached the other hemisphere, invisible from Earth.

About four hours later it disappeared completely, and we saw only the heights that it still illuminated. But they too went dim. The darkness was remarkable. A multitude of stars! You can see that many on Earth only with a decent telescope.

Their lifelessness, however, is unpleasant; their motionlessness is far from the motionlessness of the blue sky of tropical countries.

And the black background was so oppressive!

What was that, giving off such a strong light in the distance?

Half an hour later we found that it was the mountain peaks. More and more such peaks were beginning to glow.

We had to run up the mountain. Half of it was lit up. There was the Sun! But while we ran up, the peak had already had time to grow dark, and the Sun was no longer visible from it.

Apparently, this was the line of sunset.

We set off more quickly. We flew like arrows from the bow.

We could have hurried less than that: all the same we would see the Sun rising in the west, even if we ran only 5 versts per hour, that is, if we didn’t run at all – what kind of a run is that! – but walked.

But we couldn’t help rushing.

And there, O miracle!

The rising star gleamed in the west. Its size quickly increased… A whole slice of the Sun was visible… The whole Sun! It rose, grew separate from the horizon… Higher and higher!

However, that was only for us, because we were running; the mountaintops left behind us were going dark one by one.

If we hadn’t looked at those unmoving shadows, the illusion would have been complete.

“Enough, we’re tired!” the physicist cried jokingly to the Sun. “You can go off and rest.”

We sat down and waited for the moment when the Sun, setting in the ordinary way, would disappear before our eyes.

“Finità la commedia!”

We turned over and fell soundly asleep.

When we woke up we chased down the Sun again, just for the sake of warmth and light, without rushing, and we no longer let it out of our sight. It would rise and then sink, but it was constantly in the sky and warmed us without ceasing. We would fall asleep when the Sun was fairly high. As we woke up the laggard Sun would be crawling towards setting, but we would tame it in time and force it to rise again. We were approaching the pole!

Here the Sun was so low and the shadows so enormous that, as we ran across them, we got properly chilled. In general, the contrast in temperature was striking. Some elevated places were heated up to the point where we couldn’t even approach. We couldn’t run through other places, which had been lying in the shade for fifteen days or more (earth time), without the risk of getting rheumatism. Don’t forget that here the Sun, even though it was lying on the horizon, heated the rock surfaces no more weakly, but rather twice as strongly, as the Sun on Earth when it stands directly overhead. Of course, this can’t be so in Earth’s polar countries, because in the first place the power of the Sun’s rays is almost entirely absorbed by the thickness of the atmosphere. In the second place, they don’t shine on you so stubbornly at the pole: every twenty four hours the Sun and its light go around any rock in a circle, though they never let it out of sight.

You’ll say, “But what about heat conductivity? Shouldn’t the heat pass from a rock or mountain into the cold, stony ground?” I’ll reply, “Sometimes it does seep away, when the ground forms one whole with the main mass, but many granite massifs are simply cast onto the ground, regardless of their size, and only touch it or some other massif at three or four points. Through these points the heat passes extremely slowly, or better – imperceptibly. But the mass keeps heating up more and more; the rate of radiation of the rays is so slow.”

We had trouble, though, not with these heated stones, but with the very chilled valleys that were lying in shadow. They interfered with our approach to the pole because the closer we came to it the more extensive and impenetrable the shadowed spaces were.

If only the seasons of the year were more noticeable here – but there were hardly any seasons: in summer the Sun doesn’t rise higher than five degrees at the pole, while on Earth it rises five times higher.

And anyway, how long would we have to wait for summer, which would, most likely, allow us more or less to reach the pole?

And so, moving along in the same direction after the Sun and tracing a circle or, more accurately, a spiral on the Moon, we once again moved farther from the po

int that’s frozen in places with hot rocks scattered over it.

We didn’t want to freeze or to burn up either! We moved farther and farther… It was hotter and hotter… We were forced to move away from the Sun. We were forced to lag behind it, to keep from being roasted. We ran in the dark, decorated at first by a few shining peaks of mountain ranges. But then they were already gone. It was easier to run: we’d already eaten and drunk a lot.

Soon the moon, which we had forced to move in the sky, would appear.

There it was.

We greet you, o dear Earth!

We were glad to see it, no joke.

And how could we not be! We had been separated from it for so long!

Many more hours passed. Though we’d never seen those places and mountains, they didn’t attract our curiosity and they seemed monotonous. We were tired of everything – all these wonders! Our hearts were breaking, our hearts were aching. The view that was so splendid but inaccessible from Earth only exacerbated the pain of recollections, the sores of unrecoverable losses. It would have been good at least to reach our residence as quickly as possible! We couldn’t sleep! But what awaited us there, in the house? Well-known but inanimate objects, able to prick and lacerate our hearts even more.

From where did this longing arise? Before we had barely felt it. Hadn’t it been overshadowed then by our interest in the surroundings, which hadn’t yet had time to bore us – by the novelty?

Home as fast as possible, so at least we couldn’t see those dead stars and that sky, black as mourning!

Our residence had to be close by. It was here, we’d established it with astronomical observations, but despite indubitable indices we not only couldn’t find the familiar yard – we didn’t recognize even a single familiar view, a single mountain, which ought to have been familiar to us.

We walked along and searched for it.

Was it here, or there!? It was nowhere.

We sat down in despair and fell asleep.

The cold woke us up.

We restored ourselves with some food; there wasn’t much left.

Red Star Tales

Red Star Tales