- Home

- Yvonne Howell

Red Star Tales Page 6

Red Star Tales Read online

Page 6

The Sun moved almost at the same rate as the stars and lagged behind them hardly noticeably, which you can notice from the Earth as well.

The moon stood entirely motionless and wasn’t visible from our crevice, which we very much regretted, since from the darkness we could have observed it with as much success as at night, which was still far away. We should have chosen another crevice, from which we could have seen the moon, but it was too late now!

Midday was approaching; the shadows stopped growing shorter; the moon had the form of a narrow sickle, paler and paler, in proportion as the Sun moved closer to it.

The Moon is an apple, the Sun a cherry; if the cherry didn’t ever cross paths with the apple there wouldn’t be a solar eclipse.

On the Moon this comprises a frequent and grandiose phenomenon, while on Earth it is rare and nothing much: a little spot of shadow, the size of a pinhead (albeit sometimes several versts long, but what is that, if not a pinhead compared with Earth’s magnitude?). It traces a stripe on the planet, moving if one is fortunate from city to city and lingering in each of them for several minutes. Here the shadow covers either the whole Moon, or in the majority of cases a significant part of its surface, so that the complete darkness lasts for several hours…

The sickle grew even narrower and barely visible alongside the Sun…

The sickle became completely invisible.

We crawled out of our crevice and looked at the Sun through a dark glass…

Now it looked as though someone had squashed an invisible gigantic finger into the star’s shining mass from one side.

Now only half the Sun was visible.

Finally its last particle vanished, and everything was cast into gloom. An enormous shadow ran over and covered us.

But the blindness quickly lifted: we could see the moon and a multitude of stars.

This wasn’t that other moon like a sickle; this one had the form of a dark circle, surrounded by a magnificent scarlet glow, especially bright, but paler on the side where the remnant of the Sun had just disappeared.

Yes, I saw the colors of sunset, which we used to admire from the Earth.

And our surroundings were bathed in scarlet, as if in blood…

Thousands of people were looking at us with their naked eyes and through telescopes, observing the total lunar eclipse…

Familiar eyes! Could you see us?

While we were grieving here, the red wreath grew more even and beautiful. Now it lay evenly around the whole circle of the moon; this was the midpoint of the eclipse. Now one side, opposite to where the Sun had disappeared, was getting paler and lighter… Now it was getting brighter and brighter and taking on the look of a diamond set in a red ring…

The diamond turned into a bit of Sun – and the ring became invisible… Night passed over into day – and our blindness passed: the former picture appeared before our eyes… We started talking animatedly.

I said earlier, “We picked a shady spot and made observations,” but you, my reader, might well ask: “How could you observe the Sun from a shady spot?”

I would answer, “Not all the shady spots are cold and not all the lit spots are red-hot. In fact, the temperature of the ground depends mainly on how long the Sun has been heating that place. There are expanses that have only been lit by the Sun for a few hours, but were in shadow until then. Understandably, their temperature not only can’t be high, it’s even extremely low. Where cliffs and steep mountains cast shadows, there you find expanses that are still cold, though they’re lit up, so that you can see the Sun from them. It’s true that sometimes they’re not close by, and before you can get to them you get pretty heated up – even an umbrella doesn’t help.”

We noticed the multitude of rocks in our crevice and so, for our own comfort and in part for the exercise, we decided to haul those that hadn’t yet warmed up in sufficient quantity to the surface, so as to cover the space that was open from all sides with rocks and thus protect our bodies from the heat.

No sooner said than done…

That way, we could always go out onto the surface and, resting in the middle of the mass of stones, triumphantly make our observations.

Let the rocks get heated through!

We can haul out new ones, since there are so many down below; we have at our disposal plenty of strength, increased sixfold thanks to the Moon.

We executed this plan after the solar eclipse, which we had not even been certain would take place.

Besides this job, right after the eclipse we set to work establishing the latitude of our location on the Moon. This was not hard to do, keeping in mind the epoch of the solstice (which we could determine thanks to the eclipse that had taken place) and the height of the Sun. The latitude of our location turned out to be forty degrees north, meaning that we were not located on the equator of the Moon.

And so, midday passed – seven Earth days after the rising of the Sun, which we had not witnessed. In actual fact, the chronometer showed that the time of our stay on the Moon was so far equal to five Earth days. Therefore, we had appeared on the Moon early in the Moon’s morning, some time after its forty-seventh hour. That explains why, when we woke up, we found the ground very cold: it hadn’t had time to heat up, and it was terribly chilled by the previous extended fifteen-day night.

We slept and woke, and every time we saw more and more new stars above us. They were always in the same pattern, familiar from the Earth, always the same stars: only the narrow hole in which we were settled didn’t allow us to see a great quantity of them at once, and they didn’t twinkle against the black field, but passed by twenty-eight times more slowly.

There was Jupiter; here its satellites were visible to the naked eye, and we observed their eclipses. Jupiter disappeared. The North Star rolled out. Poor thing! It played no important role here. Only the Moon alone would never glance into our crevice, even if we waited a thousand years for it. It wouldn’t come out, because it was eternally immobile. It could be animated only by the movements of our bodies on this planet; then it could sink, rise and move through the sky… We would return to this question again…

You can’t sleep all the time!

We got down to making plans.

“At night we’ll come out of the crevice, not right after the Sun sets, when the ground is heated almost to the utmost, but after a few dozen hours. We’ll visit our residence too, to see what’s going on there. Has the Sun gone and broken anything? Then we’ll travel for a while by moonlight. We’ll enjoy the view of the moon here to our hearts’ content. Until now we’ve seen it looking like a white cloud; at night we’ll see it in its full beauty, in its full glory and from all sides, since it rotates rapidly and will show its whole self in no more than twenty-four hours, which is an insignificant part of the lunar day.”

Our large moon – the Earth – has phases, just like the Moon, which we had looked at previously from afar, full of dreams and curiosity.

At our present location the new moon, or rather the new Earth, appeared at midday; the first quarter as the sun set; the full moon at midnight, and the last quarter at sunrise.

We were located in a place where the nights and even the days were always moonlit. That was not so bad, but only as long as we were in the hemisphere visible from Earth. As soon as we passed into the other hemisphere, the one invisible from Earth, we would immediately lose our nighttime light. We’d be deprived of it as long as we were in that unfortunate, yet so mysterious, hemisphere. It’s mysterious for the Earth, since Earth never sees it, and therefore it intrigues the scientists very much; it’s unfortunate because its residents, if there are any, are deprived of both the nocturnal light source and the magnificent view.

In point of fact, are there any inhabitants on the Moon? What are they like? Do they resemble us? Until now we hadn’t met any, and it would be fairly hard to meet them, since we had been sitting almost in one place and spending much more time on gymnastics then on selenography. That unknown half was especi

ally interesting, with its black skies eternally covered at night by a mass of stars, for the most part tiny, easy to view by telescope, since their gentle gleam was neither disturbed by the multiple refractions of the atmosphere, nor violated by the crude light of the enormous moon.

Could there be a hollow there where gasses could gather, and liquids, and a lunar population? This occupied our conversations, which passed the time as we waited for night and sunset. We waited with impatience. It wasn’t too tedious. We didn’t forget to experiment with vegetable oil, an idea the physicist had brought up before.

In fact, we managed to collect drops of an enormous size. Drops of oil that fell from a horizontal surface would attain the size of apples, while drops from a sharp edge were significantly smaller, and oil flowed through an opening two and a half times more slowly than on Earth under identical conditions. The phenomena of transpiration took place on the Moon with sixfold strength. Thus, the meniscus of oil at the edges of a vessel rose six times higher above the level of the oil in the center.

Oil in a shot glass had the form almost of a depressed sphere…

We didn’t forget about our sinful bellies either. Every six to ten hours or so we fortified ourselves with food and drink.

We had a samovar with us with a lid that screwed on firmly, and we often sipped a strong brew of the Chinese herb.

Of course, we couldn’t put the samovar on in the usual way, since air was needed for the combustion of coals and kindling. We simply carried it out into the sun and surrounded it with especially hot little pebbles. It would heat up quickly, without boiling. Hot water poured strongly from the open spout, driven by the pressure of the steam, which was not counterbalanced by the weight of the atmosphere.

It wasn’t especially pleasant to drink this kind of tea because of the possibility of getting badly burned, for the water went in all directions like exploding gunpowder.

Therefore, after putting tea into the samovar ahead of time, we would let it heat up a lot at first, then wait for it to cool down after we removed the hot stones, and finally we would drink the prepared tea without burning our lips. But even this relatively cool tea poured out with noticeable force and boiled weakly in our mugs and in our mouths, like seltzer water.

V

Soon the sun would set.

We watched the Sun touching the peak of one mountain. On Earth we would watch this phenomenon with our naked eyes, but here that was impossible, for there was no atmosphere, nor any water vapor, and so the Sun lost none of its bluishness, nor its power of heat and light. You could only take a quick passing glance at it without a dark glass; it was nothing like our scarlet Sun that is weak when it rises and sets!

It sank, but slowly. Half an hour had already passed since it first touched the horizon, and only half the Sun was hidden.

In St. Petersburg or Moscow the sunset lasts no more than three to five minutes. In tropical countries it’s about two minutes, and only at the poles can it continue for several hours.

Finally the last particle of the Sun was extinguished behind the mountains, where it looked like a bright star.

But there was no sunset glow. Instead of a glow we saw around us a multitude of mountain peaks and other elevated parts of our surroundings lit up with bright reflected light.

This light was entirely sufficient to keep us from sinking into darkness for several hours, even if there had been no moon.

One distant peak continued to glow for thirty hours, like a streetlamp.

But then it went out too.

Only the moon and stars made light for us, and the power of illumination of the stars is negligible. Right after sunset, and even a while after, the reflected sunlight outweighed the light of the moon.

Now, when the last mountain cone had gone dark, the Moon – lord of the night – sat in state over our moon.

Let’s turn our gaze toward it.

Its surface is fifteen times larger than the surface of the Moon from the Earth, compared to which, as I already said, it’s like a cherry to an apple.

The power of its light is fifty or sixty times brighter than the Moon with which we are familiar.

We could read without straining; it seemed that this wasn’t night, but some fantastic kind of day.

Its radiance didn’t let us see either the lights of the zodiac or the smaller stars without special screens.

What a sight! Hello, Earth! Our hearts beat wearily, neither bitterly nor sweetly. Recollections burst into our souls…

How dear and mysterious now was that formerly disdained, everyday Earth! It looked to us like a picture covered with blue glass. That glass was the ocean of air around the Earth.

We saw Africa and part of Asia, the Sahara, the Gobi, Arabia! Lands of drought and cloudless skies! There were no blots on you: you are always open to the moon-dwellers’ gaze. Only when the planet rotates around its axis does it bear these deserts away.

Meanwhile, those formless shreds and stripes were the clouds.

The dry land seemed dirty yellow or dirty green.

The seas and oceans were dark, but their shades were different, depending, probably, on the degree of their disturbance and calm. Over there, perhaps, the whitecaps were plying the backs of the waves so that the sea was whitish. The waters were covered here and there with clouds, but not all the clouds were snow-white, though there were few grey ones: it must have been that they were covered by fine layers above consisting of icy crystalline dust.

The two diametrical ends of the planet were especially brilliant: those were the polar snows and ices.

The northern whiteness was cleaner and had a larger surface than the southern one.

If the clouds had not moved, it would have been difficult to tell them apart from the snow. By the way, for the most part the snows lie deeper down in the ocean of air, and therefore the blue color that covers them is darker than the same tinge over the clouds.

We saw snowy spangles of smaller size scattered over the whole planet, even at the equator – those were mountain tops, sometimes so high that the cap of snow never leaves them, even in tropical countries.

There were the Alps gleaming!

There were the heights of the Caucasus!

There was the range of the Himalayas!

The snow spots were more constant than the clouds, but they too (the snows) change, disappear and appear once again with the seasons…

With a telescope we could make out all these details… We looked in admiration!

It was the first quarter: the dark half of the Earth, illuminated by the weak moon, could be made out with great difficulty and was far darker than the dark (ashen) part of the Moon when seen from the Earth.

We wanted to eat. But before we went back down into the crevice, we wanted to find out whether the ground was still hot. We came down from the stone layer we had made, already renewed several times, and found ourselves in an impossibly overheated sauna. The heat quickly penetrated through our soles… We retreated in haste: the ground wouldn’t cool down at all any time soon.

We ate lunch in the crevice, whose edges no longer glowed, but a terrible multitude of stars was visible.

Every two or three hours we came out to look at the moon – Earth.

We could have examined it entirely in about twenty hours, if we hadn’t been prevented by the cloudiness of your planet. A few places were stubbornly covered by clouds and made us lose patience, though we hoped to see them later, and in fact we did observe them as soon as the weather cleared there.

We hid for five days in the bowels of the Moon, and if we came out then it was only to places nearby and for a short time.

The ground was cooling, and by the end of five earth days, or towards midnight Moon time, it was cool enough that we decided to undertake our journey on the Moon, through its valleys and mountains. It seemed that we hadn’t yet been in any low-lying areas.

Those darkish, enormous and low expanses of the Moon are usually called seas, although that’s entire

ly incorrect, since there’s no water there. Would we find traces of neptunic activity in those “seas” and other low areas – traces of water, air and organic life, which in the opinion of some scientists had disappeared from the Moon long ago? There is a hypothesis that all this existed on the Moon once, if it doesn’t exist now, somewhere in crevices and abysses: there was water and air, but they were sucked away, they were consumed over the course of centuries by its soil, uniting with it chemically; there were organisms – some kind of plant life of a simple order, some kinds of shellfish, because where there’s water and air, there you find slime, and slime is the beginning of organic life, at least of the lowest kind.

As far as my friend the physicist was concerned, he thought, and with good reason for it, that there had never been life on the Moon, nor water, nor air. If there were water, if there were air, then it would have been at such a high temperature that no kind of organic life would be possible.

Let readers forgive me for expressing here the personal opinion of my friend the physicist, which is not proven by anything.

Once we completed our voyage around the world, then we’d see who was right. And so, taking up our loads, which had grown considerably lighter due to the large quantity we had eaten and drunk, we abandoned the hospitable crevice and headed beneath the moon, which stood in one and the same place in the dark firmament, back to our residence, which we quickly found.

The wooden shutters and other parts of the house and its service buildings, made of the same material, had fallen apart and their surfaces had charred and peeled away, exposed to the Sun’s prolonged action. In the yard we found shards of the water barrel blown apart by steam pressure, since we had carelessly stoppered it and left it in the hot sun. There were no traces of water, of course: it had evaporated without leaving any behind. By the porch we found slivers of glass – this from the lamp, whose frame had been made of metal with a low melting temperature: it had obviously melted, and the glass panes had fallen. We found less damage inside the house: the thick stone walls had protected it. Everything in the cellar was still in good shape.

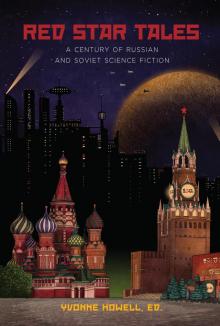

Red Star Tales

Red Star Tales